A number of indicators now suggest that the US economy may be returning to improved health, as annualised real GDP figures are expected to show growth at 3.7% (Deutsche Bank forecast) compared to a long-term trend of 3.5%, and just 2.2% since the end of the last recession.

Jobless claims are at decade lows and the US unemployment rate, running at 5.1%, suggests that the US labour market is tightening. Yet wage inflation remains stubbornly low. As we have previously highlighted the Federal Reserve has already adjusted down their estimate for NAIRU, the rate at which unemployment would trigger wage inflation. Meanwhile both part-time employment and long-term unemployment are high, which might suggest that the output gap is weighing on growth and wages. Nominal wage growth (before adjusting for inflation) is thought to be around 2%. Whilst numerous variables might contribute to this low figure, including demographic trends within labour markets and reduced bargaining power of labour globally, domestic inflation could remain low in spite of a stronger US labour market.

Any improvement in the US economy may not be of immediate benefit overseas. US imports of $2.3 trillion annually are equivalent to 16% GDP, which is a lower ratio than developed world peers in Europe and Asia. China heads the US’s major trading partners. It accounts for 20% of imports and has seen factory gate prices declining. The authorities have also begun a move to a floating rate currency, which could well see export prices fall. Amongst the major imports to the US is oil, where prices remain depressed, limiting the receipts for overseas countries importing to the US for the time being. Whilst Japan accounts for just 6% of US imports, this is equivalent to 20% of Japanese exports and so the country may be one beneficiary of a return to stronger US growth should it materialise. Whether the benefits will make their way out of the Japanese corporate sector and manifest in higher inflation remains debateable.

A stronger dollar could well be one effect of a firmer US economy, particularly if the US continues to outpace peers. Globally, central banks have been in an accommodative mode and Japan, Eurozone and China are engaged in policies which have the effect of depreciating their currencies. Dollar strength in the past has brought with it successive crises outside of North America, and emerging markets with dollar debt and rapidly declining reserves look vulnerable. This too may have the effect of slowing global growth.

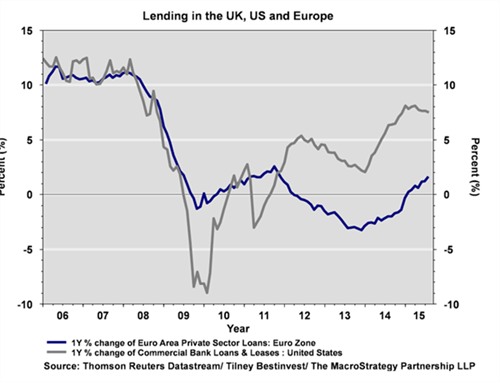

The US is supported by a domestic banking system that has gone some way towards resolution of its excesses from the previous crises, in particular in recognising loan losses against assets. As a result, bank lending and the availability of credit has improved. Meanwhile, the state of the banking system in Europe remains moribund, where bank lending growth rose by less than 1% nominal and total lending remained flat, as highlighted by The MacroStrategy Partnership LLP on Friday. The average of total bank assets in the UK and Europe is in excess of 350% GDP and banks are of much greater relative importance than their US and even Asian peers. This suggests that a recovery in European growth is likely to be several years behind the US.

Source: The MacroStrategy Partnership LLP

Conclusions

Even if the US does recover, global growth in aggregate may not follow. Europe seems unlikely to provide a positive surprise and China is slowing, having previously accounted for a significant portion of global GDP. Weak revenues in the most recent US earnings season, a downbeat outlook and poor results from cyclical sectors are signals that the global economy is impaired. Against this backdrop, it may be unlikely that investment picks up to support further growth, particularly since debt levels are high; the cost of debt servicing would increase with a higher rate cycle.

Look out for an update from us following the FOMC decision.

Sources

MacroStrategy, Centrality of Bank Lending, 10 September 2015

Deutsche Bank Research, US Economic Weekly, 11 September 2015

Permira Debt managers, BOA ML Global Research, Central Bank Data, Haver, February 2014

Disclaimer

This article was previously published on Tilney prior to the launch of Evelyn Partners.